It’s Time to Drop “Darwinism” and Listen to Darwin and His Successors on Human Evolution

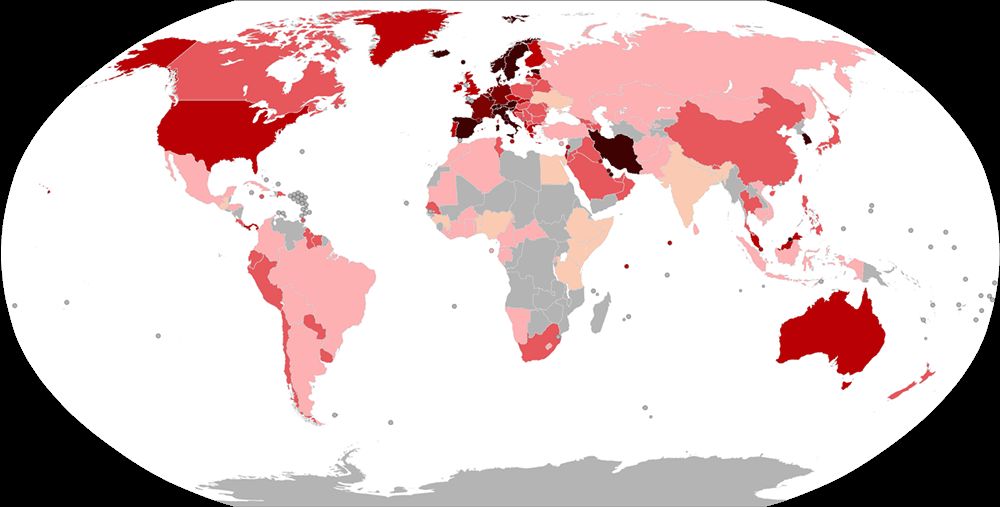

This COVID-19 crisis has politicians, financial forecasters and celebrities invoking Darwin. Whether it is Boris Johnson to promote herd immunity,Donald Trump to save the great American economy,this is purportedly done in the interests of the survival of the human race. Others are likely invoking Darwin as a salve to block out guilt regarding the thousands dying while the invoker is comfortably ensconced in luxurious social isolation. Some may invoke Darwin to make sense of the impossible choices we have forced on our healthcare workerswhen they run out of ventilators. The general message is that it is natural to sacrifice the weak to strengthen and evolve the human species. What they are actually referencing is Social Darwinism, a distortion and hijacking of evolutionary theory that was debunked in the early 20th century.

The theory of evolution has evolved significantly since Darwin. Even if it had not, there are several things that these invokers do not seem to understand.

The Fuel of Evolution

The first is that the fuel of evolutionary advance and survival is diversification or “deviation from the norm,” not survival of the fittest. The more differences or variations among the species, the greater the directional choices available for evolutionary advances. Human evolutionary advances, such as the development of language, happened when there was a relaxation of natural selection. The more choices, the more likely there will be a choice more fitting for the changing context and challenges to survival. This is especially important when the challenges are unexpected or disruptive. This is when we need choices that are furthest from the average or typical, because life is far from the norm. Whether we are talking about the evolution of our actual collective genetic make-up, our markets, or our social practices, the way forward is not the average, majority or currently popular; it is at the edge or margins. Our survival is dependent on supporting and including difference and variation. Monocultures do not survive; they can be felled by a single threat.

Who is the Fittest?

The next misunderstanding seems to be what is meant by “fittest,” when we talk about “survival of the fittest.” Most people, with any understanding of evolution, have heard the messagethat fitness does not refer to strength but to the ability to adapt. It isn’t the bullies or those with other forms of might, wealth, or security; they have far less impetus to adapt. Adaptation is prompted by difficult situations, not by comfort or complacency. People with wealth and power are cushioned from hardship and pressures to adapt. Their resourcefulness is rusty, their responsive resilience has atrophied. Large predators are also the first to face extinction.

Who are the weak?

If fitness or adaptability are at one end of the spectrum, what is meant by weakness? Logically this would imply lack of flexibility, but there is more to the misapplication of the theory of evolution. The invokers of Social Darwinism seem to imply that there is a logical value system associated with their interpretation of the theory; that the people they see as weak are less valuable to the survival of the species. That “the weak” are a necessary but acceptable sacrifice for the good of the whole.

There are many flaws in this logic, not to mention the misidentification of “the weak,” and the cold calculated plotting of human fate. However, the argument seems to accept the premise that we are a collective species, that we are not only talking about the survival of individuals but survival of our race, nation or society. This premise would lead us to ask who is of value to our survival, in a long-term systemic sense. Several authors have already made the valid argument that the polluters and exploitative robber barons threaten the human race and are of less (if not negative) valueto the survival of the species.

I would argue that there are even deeper reasons. Why do more intelligent and evolved animal communities valiantly protect their vulnerable young and old; moving them to the protected center when they are under threat? Most humans understand the value of investing in our future by protecting the defenseless young. Many cultures understand the importance of preserving the wisdom and knowledge provided only through a long lifetime of experience, by our old.

A matter of survival

I would assert that we need fragility and vulnerability in our lives. We need people who have experienced struggle, people with a variety of different and uncommon needs to help us design our world. If we respect and include others who are fragile, we are compelled to create a more generous and kinder society, a society that will treat us kindly when we are at our weakest, when we are struggling. People who have difficulty with or can’t use our current systems are needed to move us forward, most innovations we take for granted today were catalyzed by the desire to circumvent a barrier experienced due to a disability. It is the people at the margins of our society that are our stress testers, they provide the early warning signs of the things that will go wrong. They also have the most compelling reasons for innovation.

We need fragility and vulnerability in our society for our society to survive. Caring about people who are vulnerable compels us to create the conditions for surviving when we are vulnerable. This compunction gives us a larger safety net, especially in times of unexpected and disruptive hardship. The reasons we are unprepared for this crisis are because we devalued, marginalized and stopped caring for our vulnerable. The major thing that will extend this crisis is ignoring the jagged edges of our society and assuming everyone has access to water, has a home to shelter in, has room for social distancing, and has resources to wait this out. What will make it unliveable is ignoring the needs of all the workerswe have dehumanized and made invisible but that we depend upon to make our communities run. What will force us into impossible choices is our unwillingness to call on the people who think they are valuable and strong to prove their value to our society, and apply their power to benefit our species and our world as a whole.

As we prospered as a society we robbed and dismantled the commons. We lost sight of the edge, the periphery, the margins of our human scatter-plot. Science lost sight of the outliers and weak signals. Markets ignored needs without economies of scale and without large customer bases. Media ignored anything that wasn’t popular. Politics focused on the majority and the largest number of votes. Most dangerous to our survival, we are now misidentifying and willing to sacrifice “the weak.” In these times, and to prepare for the next inevitable crisis, to thrive and not just survive the turbulence, our most valuable people are the people that we have miss-labelled the “weak,” the people with lived experience of that vulnerable edge.