The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design, Part Three

This is the third part of a three part blog that describes a guiding framework for inclusive design in a digitally transformed and increasingly connected world. Part One can be found here, and Part Two can be found here. The three dimensions of the framework are:

- Recognize, respect, and design for human uniqueness and variability.

- Use inclusive, open & transparent processes, and co-design with people who have a diversity of perspectives, including people that can’t use or have difficulty using the current designs.

- Realize that you are designing in a complex adaptive system.

Inclusive design plans and facilitates change. Change in environments, products, services and processes, but also social change. By stretching the responsiveness and adaptability of the designs we live with, it supports a diversity of human knowledge, skills, and perspectives. The third dimension of inclusive design attends to the relationship between the individual/s that will be included and the larger nested complex adaptive systems they must participate in.

The Inclusive Design Paradox

Within inclusive design there is an apparent paradox. Inclusive design must hold and support both diversification and cohesion (or inclusion). It must accomplish the feat of including greater variety while keeping the whole from splintering or fragmenting. Inherent in this feat is respecting the inherent value of both the individual and the society. Counter examples would be sacrificing an individual for the good of the group, or conversely privileging an individual at the cost of the good of the group.

Inclusive design can be applied to any design, from the design of a product, a process, a service, an environment, a policy or an organization. When designing interfaces or applications attending to the challenge includes maintaining interoperability and usability while adding options or possible configurations. Within products and environments, the challenge is also to maintain a unified aesthetic while adding affordances for difference. Redesigning more inclusive services, processes, or organizational structures requires a culture change, while also sustaining social cohesion.

Navigating the Paradox

Navigating this paradox is the third dimension of inclusive design. In our increasingly connected and complex world, no design decision is made in isolation. Conversely, no design that demands change will succeed or survive unless you consider the complex adaptive system that encompasses it.

Take a student and the change required to enable greater inclusion within a classroom. The inclusive practice will require that the teacher change her teaching. This will require the cooperation of the school administration. This in turn will require the consent of the school district or board, which will in turn require the support of the educational ministry or department. If any of these nested systems does not also change there will be a misfit and point of friction. The part of the system that has changed without the context changing will bear the cost of this friction. This change burden will take a toll that threatens the survival of the inclusive design.

Take Cary, a student who relies on a switch controlled on-screen keyboard he operates with a voluntary head movement. Cary is in an integrated classroom. To optimize Cary’s learning and enable him to participate fully in his class, he requires that all the learning resources be available on his computer which he can control. The presentation of the resources (e.g., layout, size, spacing) must also be reconfigurable so he can navigate and manipulate the resource without a standard keyboard or mouse. This means that his teacher needs to be able to source all the curriculum materials in an open digital format. This implies that the school needs to support digital textbooks, learning resources and assessments. This has an impact on the procurement processes and policies of the school board or district. The implications of this change can spread all the way to the national and even global level as it affects how textbooks and teaching supports are designed and delivered.

On the other hand, this demand for a systemic change for one student, if met, can also result in greater usability, innovation, sustainability, and agility for the entire education system. It means that when the system must transition to more participatory models of pedagogy, the learning resources are in a form that students can augment and edit. They will be in a form that educators can translate, localize, augment and update. The system-wide change brings about greater agility or dynamic resiliency in the system. The system, in turn, is more prepared for a change in the world that it is embedded in, such as changes in the future of work and the demands made of its students upon graduation.

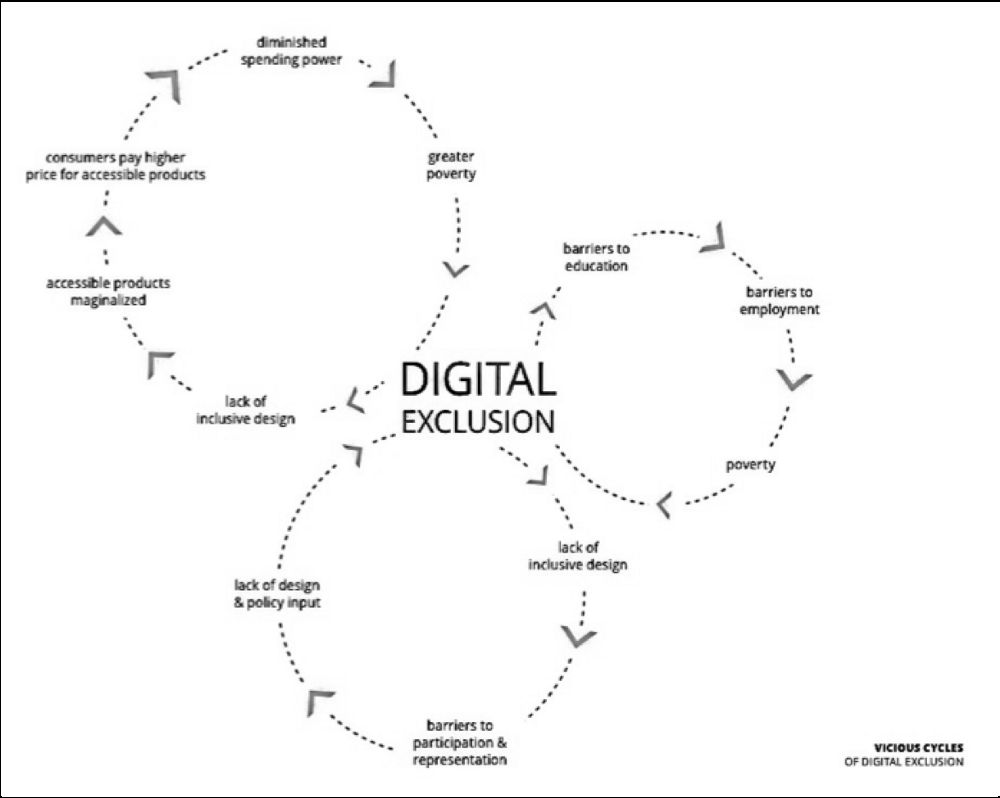

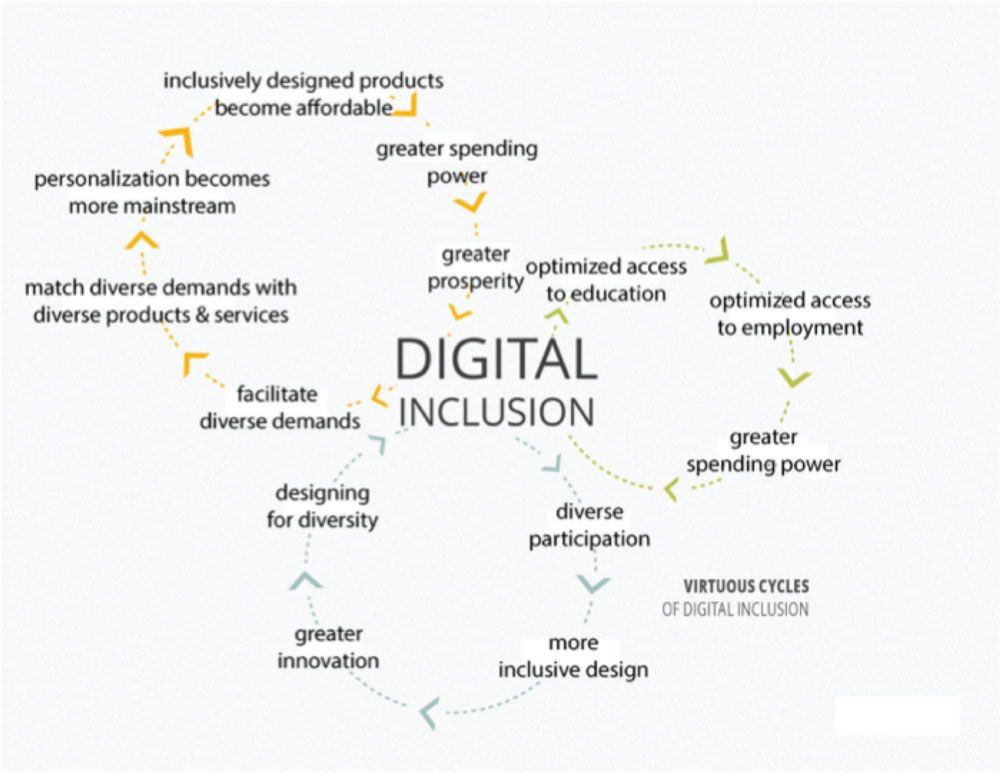

Turning Vicious Cycles Into Virtuous Cycles

The challenges, or “pain points” that inclusive design seeks to address are often embedded in and feed into vicious cycles. For Cary the student, having a disability (especially a disability that is not “high incidence”) means that he is caught in a vicious cycle of exclusion and impoverishment. Products he needs are not produced by the mainstream market, they have no economy of scale. Hence, when they are available they will cost more, be less readily available, require special skills to operate and maintain, and the likelihood that they will be compatible with the systems everyone else uses are remote. This means that access to education will be harder, this also means that employment possibilities will be more constrained, which will mean that his income is lower while his costs for essential things will be higher. The chances this will change are reduced as it is highly unlikely that he will be at the decision-making tables to advocate for his needs. It is also less likely that anyone like him can be there to represent his needs. This vicious cycle will lead to impoverishment, of opportunity as well as resources, and all the social, physical, emotional and cognitive ills that poverty brings. The vicious cycle Cary is caught in also has an impact on his family, community and society as a whole.

Interventions in Complex Adaptive Systems

However vicious cycles can be broken by strategic interventions. For example, if we require that someone like Cary be at the table when educational policy decisions are made, and also helping to co-design the educational resources, the resources he needs will be available to him, will not cost more, will be better integrated and maintained, and they will be enriched by the community of educators. He will have better access to education, which will improve his chances of employment, which will make it more likely that he can participate in decision-making in his community. Interventions in vicious cycles are more likely to survive, thrive and trigger a virtuous cycle if the context and the broader beneficial impact for the system as a whole is considered, understood and addressed in the inclusive design.

Donella Meadows, the late prescient systems thinker listed 12 ways to intervene in complex adaptive systems in increasing order of effectiveness:

- Constants, parameters, numbers (such as subsidies, taxes, standards).

- The sizes of buffers and other stabilizing stocks, relative to their flows.

- The structure of material stocks and flows (such as transport networks, population age structures).

- The lengths of delays, relative to the rate of system change.

- The strength of negative feedback loops, relative to the impacts they are trying to correct against.

- The gain around driving positive feedback loops.

- The structure of information flows (who does and does not have access to information).

- The rules of the system (such as incentives, punishments, constraints).

- The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure.

- The goals of the system.

- The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters — arises.

- The power to transcend paradigms.

Inclusive design itself can be seen as a new paradigm that requires a shift in mindset. The respect for and integration of diversity inherent in inclusive design also requires a relinquishing of a single paradigm. Within inclusive design we employ a “yes, and” response to difference.

System Behaviors

We need to keep in mind that while systems have certain common behaviors, they are just as diverse as individuals. Some will react in very unexpected ways. Have you ever played with a mixture of cornstarch and water? Unlike most fluids, this mixture will become more rigid and less viscous if you apply pressure or try to mix it too quickly. Some social systems display this non-Newtonian behavior when you trigger the social system’s defensiveness. Counter-productive values and behaviors will become more entrenched. Change that is imposed from the top, down; or change that does not involve the individuals or groups that are impacted is more likely to elicit this response. For this reason, inclusive design grows from small successes and employs organic, non-linear models of growth that engage as many perspectives as possible.

Avoiding Cobras

Our approaches need to match and consider the complexity of the issue we are addressing. The German economist Horst Siebert termed the unintended consequences of simplistic solutions for complex problems the “Cobra Effect,”after an anecdote in an Indian city during British rule. The anecdote recounts an approach taken by British colonialist who attempted to reduce the population of cobras in the city by offering a bounty on cobras. Enterprising Indians bred cobras to gain the bounty. The government assessed the effectiveness of the effort by the number of dead cobras being turned in for bounty and assumed that it was successful. When the breeding scheme was discovered, the government cancelled the bounty. The cobras, which no longer had a monetary value, were released resulting in more cobras in the city, or the opposite of the intended effect.

An example of a Cobra Effect in the realm of accessibility is the simplistic implementation of accessibility standards. I once visited a school which proudly claimed that they had made their standardized exams “fully accessible.” The student that demonstrated the exam used a single switch which he activated with the only movement he could voluntarily control to drive a cursor across the rows and columns of an onscreen keyboard. To control the movement of the cursor he needed to repeatedly select arrow keys and a select key. This meant that for each question, he would need to make up to 30 selections on the onscreen keyboard. Each selection would require multiple switch hits. Consequently, the process of operating the exam involved far more cognitive load than knowing the answers to the exam questions. However, the school had met all the Web Content Accessibility Guidelinecriterion and was therefore fully compliant to accessibility regulations and policy.

One of the activities employed in inclusive design is the “grandparent, toddler” conversation, in which, like a toddler, we continuously ask “why?” This leads to reframing the question or the problem and extending the focus to the broader causes, rather than the symptoms. Considering individuals who are currently marginalized encourages a focus on the essential elements of the system. In the example of designing inclusive learning experiences, this means considering what the learning goal is, rather than focusing on the problems with the specific instructional material.

Avoiding Polarization

A defensive phenomenon that can quickly degrade any effort is polarization. Polarization within a society tends to result in greater and greater extremes. This prevents either side from advancing because it prevents self-critique. It promotes rigid adherence to the espoused position of the side you belong to. Any self-criticism or proposals for alternative strategies are viewed as causing vulnerability and as providing the opposite side a target for attack. Rather than welcoming constructive critique, each side uses blame to fortify the polarity that they are defending, so that neither side evolves.

As mentioned in Part One, inclusive design is itself an antidote to polarization. I liken it to a pendulum, the further you push it in one direction the further it swings in the opposite direction. Add one or more sideways pushes or diverse perspectives to the pendulum and it stays away from the extremes. Employing another physical image, if you have a platform balanced on a point, the best way to keep it balanced or in equilibrium is to distribute many weights across the whole platform. If you have this diverse distribution, the impact of the loss of one weight won’t have as catastrophic an effect. An inclusively designed system recruits the energy and participation of many agents, coming from many perspectives to push the pendulum or balance the platform.

Riding Waves and the Last Frontiers

Some anthropologists, who take a long view of change, have encouraged optimism regarding the fate of rigid social structures that exclude: “Much of recent history can be seen as waves of tolerance and acceptance breaking against the rocky headlands of rigid social structures. Though it can seem to take almost forever, the waves always win in the end, reducing immobile rock to shifting sand. The twentieth century saw headlands beginning to crumble under surges of anti-slavery movements, women’s rights, racial equality, and more recently, the steadily growing acceptance of the rights of gay, lesbian, transgender, and bisexual people.”

Including difference is how we evolve as a human society. Inclusive design is about far more than addressing disability. But disability has been called our last frontier. It is the human difference that our social structures have not yet integrated. This is paradoxical because disability is a potential state we can all find ourselves in. If we reject and exclude individuals who experience disabilities, we reject and exclude our future selves and our loved ones.

The Change Workers

People at the margins are most vulnerable to the negative consequences of an unhealthy system. However, change and innovation happens at the edge. The individuals that find themselves at the margins of our society can be seen as our change workers. If we abandon and disenfranchise our change workers, we risk the survival of our society. Stasis is not sustainable. Closing off difference threatens the system. As we know from the Second Law of Thermodynamics: “closed systems inexorably become less structured, less organized, less able to accomplish interesting and useful outcomes, until they slide into an equilibrium of gray, tepid, homogeneous monotony and stay there” (Steve Pinker). A homogeneous system can be felled by a single threat. Integrating difference and supporting members when they are vulnerable leads to a self-healing system that fosters a richer array of responses to the inevitable unexpected threats that arise.

Collective Flow

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the author of Flow, asserts that the self grows by becoming more complex, which is the result of two processes: differentiation and integration. Applying this notion to society as an entity, this implies combining the movement toward optimizing individual uniqueness while maintaining social cohesion and collaborative integration of skills. A cooperative system of humans with a well-coordinated set of diverse areas of expertise will likely achieve something more complexly challenging than a single generalist or a team of people with similar specializations. The key to this collective state of flow is collaboration and integration. Given the complexity and shifting nature of our world this collaboration needs to be dynamic and responsive.

Our understanding and social skills in collaboration are poorly developed, especially when addressing complex, unpredictable challenges. Our education systems, business practices, and politics favor competition over collaboration. We have come to equate cooperative societies with communism and equality with sameness. Neither fosters difference. When we think of coordination we often think of rigid, hierarchical structures with conscripted roles, confined responsibilities and blinkered domains of interest. These are most often hostile to people that are different.

As researchers in biomimicryhave discovered, we can find more advanced forms of collaboration and coordination in natural ecosystems. Our advanced, but relatively extremely young and immature species can learn much from the rest of the inhabitants of this globe. Many researchers have become fascinated with the set of simple rules each member follows in a hive or ant colony to achieve very complex collective outcomes. The Golden Rule may be a human version of a simple rule that sustains our human society. We also continue to discover the many wondrously woven symbiotic relationshipsbetween the other members of our world.

The Power of Potential

Our society’s favoring of perfection and completion is a form of rigidity that disenfranchises difference. I have promoted the notion of Wabi-Sabiin learning and in design. Wabi-Sabi is the Japanese aesthetic that values the imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. Incompleteness and imperfection invite participation. Impermanence welcomes change and renewal. We learn far more from failure and mistakes than from success. Appreciating and seeking constructive critique is a rare but powerful skill. Most importantly, potential has far more power than perfection in bringing about positive change.

In Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter, Terrence Deacon provides a compelling proposal for rethinking the frame of natural sciences to integrate the realm of “absential” experiences, so we can explain life, integrate value, and navigate our way out of the existential crisis our human society finds itself in. In his words: “… there is more than what is actual. There is what could be, what should be, what can’t be, what is possible, and what is impossible.”

Responding to Macauley, the British colonialist who suppressed indigenous languages in India, Poile Senguptathe Indian playwright eloquently presents the redemptive potential of inadequacy. Speaking about the inadequacy of the imposed English language to express the rich knowledge that is yet to be expressed “words I use are inadequate, an approximation. But that I realise the inadequacy is my victory too, the wealth that sustains me. Do you hear me Macaulay, I have my revenge after all. Across the land and water, over hills and desert, language is a travelling. It can never arrive.”

The German philosopher Hans Vaihingerlinked this idea of “what could be” to our social actions in his philosophy of “As If.” To act as if a state that we hope to bring about exists. Adrienne Clarksonapplies this philosophy to fostering belonging in new members of a society, in her Massey Lecture. To call forth a leap of the imagination into the realm of possibility, especially when people disappoint us and we feel our society is failing. “When we behave As If we care about each other. As If we encourage everyone to be part of the group. As If we are all equal, we are actually living a metaphor….when we live As If, the As If can become the actual reality.”

The Inclusion Challenge

Inclusive design recognizes that diversity is our greatest asset and inclusion is our greatest challenge. To meet this challenge, we must consider the many nested complex adaptive systems that make up the complex adaptive system of systems that is our world. One key to that challenge is recognizing the individual potential in all of us and the awesome potential that we can realize when we include and integrate our collective differences.